God I feel guilty. I promised you more calligraphy ages ago and I never coughed up.

Please release me from the promise? See, my joints are not as recovered as I thought. And work is going to eat a lot of my pain tolerance for at least the next 12 months.

But I will calligraph for you when I can. And for now, you can at least have the story behind my icon!

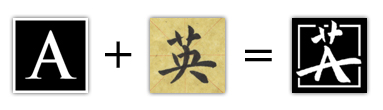

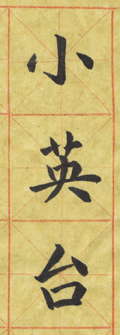

First, it’s not a real Chinese character. Sorry! But it’s even better. It’s a combination of the first character of Yingtai and the first letter of Abject.

As my long-time readers know, the original icon for this website was simply a box around the A in Abject Submission. I really liked it, because for me it was The Scarlet Letter in BDSM colours. That book was about adultery in Puritan times, but it captured the totally unnecessary shame I felt about my sexuality, and the long years of hiding in plain sight.

But fifteen years ago, before attending my first munch, I wanted a name that didn’t hide my ethnicity, and I still feel that way. English is my best language, but it’s not my first language. When you meet me it is absolutely impossible to forget that I am Not American. And this website was not reflecting that sufficiently.

So I was thrilled when I realised that I could put the A of Abject into the Ying of Xiao Yingtai!

And the BDSM colour scheme remains totally appropriate! The most venerable classics of Chinese calligraphy are white-on-black stone rubbings.

I thought I picked the name Yingtai because it’s something everyone can pronounce. But in retrospect, it’s much more likely that I picked it because I was absolutely obsessed with the legend of Zhu Yingtai and Liang Shanbo as a little girl. It’s our equivalent of Romeo and Juliet.

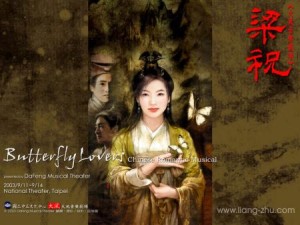

Here is my mother’s version of the Butterfly Lovers’ story, with a couple of details supplied by Wikipedia and Why Hangzhou. Warning, it’s a tragedy.

~+~

Zhu Yingtai loved books. But she couldn’t go to school. In the old days, upper-class Chinese women were allowed out of the house precisely twice a year to honour the dead. School wasn’t worth the risk.

But dammit, Wansong Academy in Hangzhou was calling her name.

Zhu Yingtai’s solution was quintessentially Chinese. Having begged her father unsuccessfully, she addressed his very real concerns about her safety and reputation by disguising herself as a young man and paying him a visit. It worked. She got permission.

And on her way to Hangzhou, who should she meet but Liang Shanbo, a personable and brilliant fellow student just a little older than her?

They felt an instant bond. The thing to do in a situation like that was to swear brotherhood on the spot. And so they did.

At this point, my mother always has way too much fun remembering the various improbable stunts that poor Zhu Yingtai pulls when she realises that she has committed to living in close quarters with A Man. Her Modesty Is Under Threat. Liang Shanbo is puzzled but adorably clueless about his new little brother’s eccentricities.

Zhu Yingtai fell hard for Liang Shanbo, of course. They were classmates for three years, and then she got a letter from her father summoning her home.

Both young people were devastated, even though Liang Shanbo thought he was only losing his best friend. In the old days, you showed how much you didn’t want someone to go by seeing them off. For 18 miles on foot, in this case.

By now discretion was no longer Zhu Yingtai’s highest priority. She had a very good idea of why a young woman might be summoned home just before reaching unmarriageable age, and she devoted the entire trip to the task of hinting her gender and feelings to Liang Shanbo. (I guess modesty was still a priority, because just telling him was evidently not an option.)

And of course, he still didn’t get it. (Adorable chump.) Finally, in desperation, she proposed marriage – on behalf of her sister, whom she guaranteed to be just like her.

Liang Shanbo promised to visit later and follow up. Marrying female relatives was a pretty common way of cementing male friendships. But when the idiot saw her family mansion he decided that such a rich family would never entertain a poor student like him. He went away.

Zhu Yingtai is betrothed against her will.

Liang Shanbo finds out who his best friend’s sister really is, with predictable results. Heartbreak. Decline. Death. Which is really too bad, because he has now passed the Imperial examinations and is an eminently eligible official.

Zhu Yingtai decides there is no longer any point in resisting the arranged marriage. But she does ask for one favour, and it’s granted. The bridal palanquin carrying her to her new husband’s house stops at Liang Shanbo’s grave and she gets down to kowtow.

(Women do not normally kowtow to lovers in Chinese tradition, but the dead outrank everyone else.)

And a miracle happens. The grave opens up. So of course, she throws herself into it. The grave closes, and two butterflies appear and flutter away together.

And they lived happily ever after.

~+~

I agree. This is not the most wholesome model for true love.

But I do find it instructive to compare the Liang Zhu legend with Romeo and Juliet. On the Chinese side, filial but headstrong bookworm falls for brilliant but humble classmate who makes good. On the Western side, killer playboy falls for thirteen-year-old nymphet with passionate disregard for both families.

I honestly prefer the values of my own heritage here. And not just because of the kowtowing. Which, according to my mother, I used to re-enact endlessly when I was a little girl. Hey, you have to practise paying your respects to your true love, right? [cough]

In all seriousness, it’s not the self-immolation that resonated with me when I picked this name. It was the terror of discovery. I don’t know when I stopped trying to repress all signs of submissiveness in vanilla life. Thank God I’ve stopped being afraid like that.

~+~

At this point, the observant reader may have noticed that I didn’t name myself Zhu Yingtai, but Xiao Yingtai. Literally this means Little Yingtai, but a better translation might be Yingtai the Younger.

It sounds ridiculously conceited to my ears. This is really the kind of epithet that should be bestowed by others. But my Chinese simply isn’t good enough to morph it as demanded by our actual naming conventions. And I am a cultural mongrel. Taking an ethnically correct name and feeding it into a different naming tradition makes sense, right? [cringe]

If you want more of the Liang Zhu legend, you are in luck. It has inspired countless plays, films, operas and more. (One wonders about the origin of Yentl, too.) Perhaps most accessible to non-Chinese speakers is the Butterfly Lovers’ Violin Concerto, a triumph of cultural fusion which retells the legend in traditional Chinese music using Western musical instruments.

I was delighted to discover that you can buy a subtitled version of the old film I learnt my kowtowing from, The Love Eterne. Apparently I was not the only obsessed fan; it was a box-office sensation comparable to Gone with the Wind.

If you’ll excuse me, I’ll go order it now so I can brush up on the kowtowing. It’s such a shame that none of my doms has ever allowed me to present like this.

But I live in hope!

It’s great to hear the story behind your glyph. At first it reminded me of the symbol for tea, but this is way better.

Thank you! I was feeling guilty about not enough BDSM in this post. So it’s a great relief to hear that you think it’s worth reading about anyway. :)